Rowan University Rowan University

Rowan Digital Works Rowan Digital Works

Theses and Dissertations

2-26-2015

Is Rowan University's Alcohol and Other Drugs Policy effective at Is Rowan University's Alcohol and Other Drugs Policy effective at

deterring students from possessing or using drugs and drug deterring students from possessing or using drugs and drug

paraphernalia? paraphernalia?

Amy LoSacco

Follow this and additional works at: https://rdw.rowan.edu/etd

Part of the Criminology and Criminal Justice Commons

Recommended Citation Recommended Citation

LoSacco, Amy, "Is Rowan University's Alcohol and Other Drugs Policy effective at deterring students from

possessing or using drugs and drug paraphernalia?" (2015).

Theses and Dissertations

. 260.

https://rdw.rowan.edu/etd/260

This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Rowan Digital Works. It has been accepted for inclusion

in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Rowan Digital Works. For more information, please

contact graduateresearch@rowan.edu.

IS ROWAN UNIVERSITY’S ALCOHOL AND OTHER DRUGS POLICY

EFFECTIVE AT DETERRING STUDENTS FROM POSSESSING OR USING

DRUGS AND DRUG PARAPHERNALIA?

An Evaluation Study

By

Amy N. LoSacco

A Thesis

Submitted to the

Department of Criminal Justice

College of Humanities and Social Sciences

In partial fulfillment of the requirement

For the degree of

Master of Arts

at

Rowan University

February 24, 2015

Thesis Chair: Joseph Johnson, Ph.D.

© 2015 Amy N. LoSacco

Dedication

I would like to dedicate this manuscript to my family, especially Jeff.

iv

Acknowledgements

This would not have been possible without my thesis advisor, Joe Johnson,

pushing me to find the perfect topic and seeing it through to the end. I would also like to

thank all of the committee members who took time out of their days to make my thesis

work worthwhile. I am heartily thankful for Joe Mulligan who has helped me from

developing a topic, finalizing my study, and everywhere else in between. Lastly, I offer

my sincere appreciation to all of those who have helped and supported me in the

completion of this project, including my parents who seem to think that any topic I

choose is the best one.

v

Abstract

Amy LoSacco

IS ROWAN UNIVERISTY’S ALCOHOL AND OTHER DRUGS POLICY EFFECTIVE

AT DETERRING STUDENTS FROM POSSESSING OR USING DRUGS AND DRUG

PARAPHERNALIA?

2015

Joseph Johnson, Ph.D.

Master of Arts in Criminal Justice

The purpose of this thesis is to evaluate Rowan University’s current Alcohol and

Other Drugs Policy. Two surveys were distributed; one via email to all current Rowan

University students and the other via email to all students found in violation of the drug

policy between 2005 and 2011. Three hypotheses were examined. The first was that

students generally do not know about the policy and its possible sanctions. The second

hypothesis was that the potential sanctions of the drug policy do not deter the general

student population. The third hypothesis was that the imposed sanctions help to prevent

recidivism among offenders. Results showed that the first hypothesis was false; the

general student body is aware of Rowan’s drug policy and its possible sanctions. The

second hypothesis was not necessarily true or false; it was undetermined if the potential

sanctions of the drug policy deterred the general student population. After surveying

drug policy violators, the third hypothesis was also found to be false; the imposed

sanctions of Rowan’s drug policy did not help to prevent recidivism among offenders.

Recommendations for policy change and future research were given.

vi

Table of Contents

Abstract v

List of Tables x

Chapter I: Introduction 1

Statement of the Problem 1

Significance of the Problem 5

Purpose of the Study 7

Research Questions 9

Organization of the Study 10

Chapter II: Review of the Literature 12

The Thought Behind Student Misconduct 12

The History of Student Conduct 13

Drug Free Schools and Communities Act 14

Deterrence Theory 16

Restorative Justice Practices 20

Rowan University Policies vs. Other Schools’ Policies 24

Distribution of Policies: Rowan vs. Binghamton University 29

CAS Assessment Tool 31

Summary of the Literature Review 33

vii

Table of Contents (Continued)

Chapter III: Methodology 35

Introduction 35

Context of the Study 35

Sampling 36

Instrumentation 38

Operational Definitions 41

Operationalizing Deterrence and Recidivism 42

Variables- Survey 1 44

Variables- Survey 2 52

Open-Ended Questions- Surveys 1 & 2 68

Data Analysis 69

Preliminary Data Analysis: Cross Tabulations 69

Zero-Order Correlations 70

Mann-Whitney U Tests 72

Content Analysis 75

Chapter IV: Findings 78

Introduction 78

Descriptive Statistics: Cross Tabulations 78

Research Question 1 84

viii

Table of Contents (Continued)

Zero Order Correlation 85

Mann-Whitney U Test 90

Research Question 2 94

Zero Order Correlation 95

Qualitative Content Analysis 102

Research Question 3 107

Qualitative Content Analysis 109

Other Findings 114

Chapter V: Summary, Discussion, Conclusions, and Recommendations 115

Summary of the Study 115

Discussion of the Findings 115

Recommendations for Practice 118

Recommendations for Further Research 123

Conclusions 125

List of References 126

Appendix A: General Student Population Survey 134

Appendix B: Student Drug Policy Violators Survey 142

Appendix C: Student Code of Conduct 154

Appendix D: Alcohol and Other Drugs Policy Guide 179

ix

Table of Contents (Continued)

Appendix E: Correlations Table for All Variables 205

x

List of Tables

Table Page

Table 1 Marijuana Related Charges at Binghamton University 26

Table 1.1 Illegal Prescription Drug Charges at Binghamton University 27

Table 1.2 Other Drug Charges at Binghamton University 27

Table 2 Frequency Distributions for the Independent and Dependent Variables- 45

General Student Pop. (N = 98)

Table 3 Frequency Distributions for the Independent and Dependent Variables- 53

Drug Policy Violators (N = 18)

Table 4 Open-Ended Questions Utilized in Surveys 1 & 2 68

Table 5 Cross Tabulation for SCC Read and Gender- 79

General Student Pop. (N = 98)

Table 6 Cross Tabulation for SCC Read and Class standing- 79

General Student Pop. (N = 98)

Table 7 Cross Tabulation for Chance of caught and Gender- 80

General Student Pop. (N = 98)

Table 8 Cross Tabulation for Chance of caught and Class Standing- 81

General Student Pop. (N = 98)

Table 9 Aware of Policy and Gender- General Student Pop. (N = 98) 82

Table 10 Aware of Policy and Class standing- General Student Pop. (N = 98) 82

Table 11 Deterrence and Gender- General Student Pop. (N = 98) 83

Table 12 Deterrence and Class standing- General Student Pop. (N = 98) 84

Table 13 Correlation Coefficients Between Aware of Policy 86

and Independent Variables

Table 14 Mann-Whitney U Test for Drug Policy Awareness 93

Table 15 Correlation Coefficients Between Deterrence and Independent Variables 96

xi

List of Tables (Continued)

Table Page

Table 16 Additional Comments in Survey 2 (N = 18) 112

1

Chapter 1

Introduction

Drug use in the United States has been an epidemic for several decades (Musto,

1991; McNamara, 2011). As a result of the war on drugs for the past 100 years, many

laws have been enacted to prevent the distribution and use of both drugs and drug

paraphernalia; this is mostly due to their potential overuse and harmful effects

(McNamara, 2011). The contemporary war on drugs, which began in 1971 with a

declaration from President Nixon and which is still continuing today, has focused a lot on

marijuana use, more specifically, marijuana use among college youth. Due to the on-

going war on drugs, colleges and universities have built policies to prohibit the

possession and use of both drugs and drug paraphernalia. While there are plenty of

helpful studies out there, Rowan University’s policies have not been empirically

evaluated fully (CAS, 2009a; CAS, 2009b; Johnston et al., 2008). In the subsections to

come, I will state the problem, talk about the significance of the problem, discuss the

purpose of the study and state the three research questions for this study.

Statement of the Problem

Medical historian Dr. David Musto claims that the war on drugs started roughly

100 years ago (McNamara, 2011). Cocaine became one of the most popular drugs in the

United States between 1905 and 1930 (Musto, 1991). During the 1920’s, smoking

marijuana became a great pastime for Americans and heroin became exceedingly popular

in the 1950s (Musto, 1991). There was a surge in all kinds of drug use during the 1960s

before marijuana became popular again in the 1970s (Musto, 1991). As a result of the

2

rise and fall in drug trends, many harsh policies against drug use have been enacted

(Musto, 1991; McNamara, 2011).

The war on drugs has consistently included or involved college students (U.S.

Department of Health and Human Services, 2011; Skiba, 2000; McNamara, 2011; Musto,

1991). Although “club drugs” (stimulants and hallucinogens such as ecstasy,

methamphetamine, and ketamine) were popular in the past, marijuana and alcohol have

been at the forefront for at least the last fifteen years (Simons, Gaher, Correia, and Bush,

2005). More recently, the National Survey on Drug Use and Health found that in 2010,

the rate of substance abuse among 18 to 25 year-olds is almost three times higher than

that of adolescents between the ages of 12 and 17, and adults over the age of 26 (U.S.

Department of Health and Human Services, 2011). Many harsh drug policies have been

created as a result of the drug use among college students.

In particular, Rowan University, located in Glassboro New Jersey, enacted a

policy that some students believe to be very severe (Simmons, 2010). The Alcohol and

Other Drugs Policy (2007) states that possession, use, manufacture, distribution or sale of

illegal drugs and drug paraphernalia is prohibited (see Appendix D).

1

In addition,

according to Rowan University’s drug policy, being under the influence of any illegal

drug is prohibited. If a student violates Rowan’s drug policy guidelines, they must face

judicial sanctioning. Some students consider the sanctions associated with Rowan’s

current drug policy too harsh.

In response to harsh drug policies and sanctions, grassroots movements have

1

The policy is formally entitled Rowan’s “Alcohol and Other Drugs Policy” but will be referred to here as

Rowan’s “drug policy.”

3

formed against specific laws and college/university policies. In 2011, a group of Rowan

University students, led by Eric Naroden, officially joined the national organization

“Students for Sensible Drug Policy (SSDP)” (Students for Sensible Drug Policy, 2013).

SSDP started in 1998 because students disagreed with the “counterproductive Drug War

policies, particularly those that directly harm students and youth” (Students for Sensible

Drug Policy, 2013).

On the Facebook Fan Page associated with the Rowan University SSDP chapter,

they describe themselves as a “grassroots, student-led organization comprised of

thousands of students on hundreds of high school and college campuses across the United

States and internationally” (Simmons, 2010). One of the mission statements for the club

reads:

We recognize that the very real harms of drug abuse are not adequately addressed

by current policies… we also believe that individuals must ultimately be allowed

to make decisions for themselves as long as their actions do not infringe upon

anyone else’s freedoms or safety.

The SSDP strives to make Rowan's current policy and its sanctions less punitive and

more educational. One of the reasons why students are upset with Rowan’s current drug

policy, and why they started an SSDP chapter at Rowan, is because a student can lose

housing on their first illicit drug offense (Mulligan, 2011).

As per the Student Code of Conduct (see Appendix C), a student can get their

housing suspended if caught with any type of illegal drug or drug paraphernalia. More

specifically, the policy states that for a first violation of the drug policy, as it pertains to

the use or possession of illegal drugs or drug paraphernalia, the recommended sanction is

a $400 fine, completion of substance screening, community restitution hours, disciplinary

4

probation, suspension of campus housing privileges, and parent/guardian notification

(Mulligan, 2011).

On October 11, 2011 the Students for Sensible Drug Policy (SSDP) erected a

“Box City,” where students slept in cardboard boxes from 6pm-6am outside of the

Student Center (a central location on Rowan’s campus). The goal of the protest, however

unsuccessful, was to put an end to residence hall evictions due to students’ use of illegal

drugs on campus. The Students for Sensible Drug Policy at Rowan University also

believe that the policy should be changed so that it no longer allows equal punishment for

students using illegal drugs, possessing illegal drugs, and possessing drug paraphernalia

(Simmons, 2010). It is clear from testimonials that some students do not agree with the

current policy, however, there is little empirical research that examines student

satisfaction of Rowan’s drug policy (Simmons, 2010).

Some schools have in fact begun to shy away from harsh, punitive sanctions and

have integrated restorative and therapeutic justice practices into their judicial processes.

Newbery, McCambridge, and Strang (2007) conducted a study at a London college in

which students participated in motivational interviewing (MI). MI is a counseling style

that encourages participants to evaluate actual or potential behavior in accordance with

their own values and beliefs within a constructive atmosphere (Newbery, et al., 2007).

“Let’s Talk About Drugs” was the title chosen for the on-going meetings, which used MI

to focus mainly on alcohol, cigarette, and marijuana use (Newbery, et al., 2007). At the

end of the study, qualitative feedback was collected from both the students and the Dean

of Students; feedback was positive (Newbery, et al., 2007). Students connected most

with the special events that were put on, however, they also enjoyed the in-class activities

5

and appreciated the drug education posters put up in the school (Newbery, et al., 2007).

In 2001, California Proposition 36 similarly implemented drug prevention

techniques while simultaneously focusing on therapeutic jurisprudence (Wittman, 2001).

Many other states, and specifically colleges and universities, have implemented

restorative justice techniques and lessened the sanctions for drug violations (Karp, 2013).

Rowan University has not yet done this and, therefore, it is beneficial to determine if

Rowan’s drug policy is currently effective in preventing recidivism or if other techniques

should be incorporated into the judicial hearing and sanctioning process. Surveying

students about their satisfaction with the current drug policy, whether or not they believe

the currently policy is effective, and if they think other techniques should be brought in to

take the place of the current policy, will help to gain insight on the student satisfaction of

Rowan’s current drug policy. Up to this date, little research has been done on Rowan

University’s judicial process.

Significance of the Problem

The Students for Sensible Drug Policy club at Rowan has provided anecdotal

information on student dissatisfaction, however, in addition to collecting student

perception research, the effectiveness of such policies needs further examination

(Simmons, 2010). As the literature suggests, policies and programs should be evaluated

for effectiveness (Musto, 1991). Yet, the evaluative aspect of students’ satisfaction with

college or university-wide policies and their sanctions, in addition to the policies and

sanctions effectiveness, seem to be very minimal.

The Alcohol and Other Drugs Policy Guide (see Appendix D) states that Rowan

6

will review the Alcohol and Other Drugs Policy and educational programs every two

years for effectiveness, to guarantee that the disciplinary sanctions are enforced

consistently, and to implement changes if needed (Rowan Student Handbook, 2011).

This will be done via a committee of faculty, staff, and students in conjunction with

Student Life and the Office of Human Resources (Rowan Student Handbook, 2011).

However, these reviews are not made publically available online and when asked if

Rowan University studied the drug policy for effectiveness, these reviews were not

mentioned. Rowan did, however, recently conduct a onetime, cross-sectional evaluation

of its drug policy in terms of recidivism rates. This was done solely by looking at the

number of students who have been found responsible, by Rowan, for violating the drug

policy more than once; that research has historically omitted the students who have

continued to violate the policy without being caught (Mulligan, 2011). This lack of full

research does not only apply to Rowan University. In fact, when asked via email in

January of 2012, many college/university administrators working in student conduct

replied that they were not aware of their policies ever being evaluated from the student

conduct perspective.

2

Further assessment of the drug policies at colleges and universities is much

needed. Dannells (1997: 2) discusses the importance of evaluating student conduct

policies, “First, institutional research should be done on existing disciplinary programs to

determine their present effectiveness. Like any other student development program, these

efforts should be periodically and systematically evaluated to ensure they are meeting

2

These schools included The College of New Jersey, Stockton University, Rider University, La Salle

University, Arcadia University, Temple University, Drexel University, West Chester University,

Kutztown University, and Pennsylvania State University.

7

their goals.” If Rowan’s drug policy does not meet their goals by having a deterrent

effect on its students, it should be reorganized in order to increase effectiveness and

improve the wellbeing of the students it seeks to serve. Also, the Council for the

Advancement of Standards in Higher Education (2009a: 5) states, “Not every program is

right for each campus, but through intentional programming and thorough assessment,

ineffective programs can be discarded, effective ones retained, and new programs added.”

Without proper assessment, the University will be unaware of if they need to change the

policy or maintain it. This evaluation is necessary in finding out student awareness of the

drug policy at Rowan University, their opinions of the policy, and the effectiveness of its

current punishments, in regards to the true recidivism rate.

Purpose of the Study

According to the most recent National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH,

2011: 22), “In 2010, the current use of illicit drugs was 22.0 percent among full-time

college students aged 18 to 22.” Presumably, some college students only partake in

recreational drug use; however, many students aged 18-22 are classified as drug abusers

(U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2011). The NSDUH reports that in

2010, the rate of substance abuse among 18 to 25 year-olds (19.8%) is almost three times

higher than that of adolescents between the ages of 12 and 17 (7.3%) and that of adults

over the age of 26 (7%) (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2011).

College Prowler (2012) shows that the perception of Rowan University is not

much different. College Prowler is a website that offers information that is written for

students by students regarding different colleges and universities’ drug prevalence. One

8

of the features of this website is a letter grade that is given to colleges regarding their

level of “drug safety.” This grade is mostly based on the students’ perceptions of the

prevalence and importance of illicit drug use and underage drinking on campus, in

addition to the amount of peer pressure that is in existence regarding alcohol and other

drugs (College Prowler, 2012). Paid student authors obtain the information by

distributing surveys to their college peers (College Prowler, 2012). Additionally, students

who can verify that they are from a specific college can answer open-ended questions

about their school on the College Prowler website. The letter grade given by the website

also incorporates statistical data from the U.S. Department of Education and schools’

own websites (College Prowler, 2012).

Rowan received a drug safety score of C, which is lower than most New Jersey

schools including Montclair State University, The College of New Jersey, and Rutgers

University (College Prowler, 2012). Out of the eleven different drugs listed, the most

popular drugs at Rowan University are shown to be alcohol and marijuana (College

Prowler, 2012). According to the student survey poll on College Prowler (2012),

marijuana is just as prevalent on Rowan’s campus as alcohol.

While College Prowler shows that alcohol and marijuana are the most popular

drugs on Rowan’s campus, it is important to also look at the Clery numbers. The “Crime

Awareness and Campus Security Act,” which was later renamed to “Jeanne Clery

Disclosure of Campus Security Policy and Campus Crime Statistics Act,” mandates that

college and universities publically report data for all on-campus crime. Clery numbers

for Rowan University show similar data to that of College Prowler; the arrests for alcohol

related offenses and other drug related offenses have been extremely close in number for

9

2009, 2010, and 2011 (Rowan University Police, 2012). Yet, the number of referrals for

alcohol was exceedingly higher than the number of referrals for other drugs in those same

years (Rowan University Police, 2012). Unfortunately, the number of illicit drug offenses

in 2011 was much higher than the previous two years. The number of illicit drug arrests

occurring on-campus or on an adjacent public property went from 38 in 2009, to 36 in

2010, and 47 in 2011 (Rowan University Police, 2012).

The war on drugs, which has always included college students, has been prevalent

at Rowan University. Although college and university drug policies have been created as

a result of the current war on drugs, it seems that Rowan’s current drug policy may not be

limiting the number of illegal drug incidents that are occurring on Rowan’s campus. The

purpose of this study is to examine Rowan University’s Alcohol and Other Drugs Policy

because many college and university policies have not been fully evaluated (U.S.

Department of Health and Human Services, 2011; Skiba, 2000; McNamara, 2011; Musto,

1991). More specifically, this study will evaluate the students’ awareness of Rowan

University’s drug policy, their satisfaction with the current drug policy, and if it is

effective, in regards to the recidivism rate, or if other techniques should be explored.

Research Questions

Throughout this study, three research questions guided the analysis:

1. Do students know about Rowan University’s drug policy and its possible

sanctions?

2. Do the potential sanctions of Rowan’s drug policy deter the general student

population?

10

3. Do the imposed sanctions help to prevent recidivism among offenders of

Rowan’s drug policy?

Organization of the Study

Chapter II contains the structural framework of the study. Within the literature

review, discussion begins on the background of college and university policies. The

literature review also explains the variance among college and university drug policies in

addition to the potential importance of how such policies are distributed. Deterrence

theory is thoroughly examined, as well as, the link between level of punishment, e.g.

getting evicted from on-campus housing, and perception of punishment as they pertain to

deterrence. Finally, literature on the effects of deterrence-based policies shows that there

may be a need for more restorative justice-based policies.

Chapter III describes the methodology of the study. This chapter begins by

offering context in describing the setting of the study, the study design, such as the use of

two surveys, and the sampling techniques that were used. The data analysis is described

in this chapter and shows the procedures used to operationalize recidivism and

deterrence, in order to get more accurate results. Finally, the hypotheses were thoroughly

explained.

Chapter IV provides the findings of the study. The profiles of respondents are

separated by each of the surveys. There is then discussion of the evidence found to either

support or contradict each of the three hypotheses. Chapter IV also displays some of the

open-ended answers from the respondents and shows other findings from the research.

Chapter V completes the study by providing concluding information based on the

11

results found. Practical recommendations are stated in order to better assist the current

practices of Rowan University. Research recommendations are also provided should

there be interest in continuing the study.

12

Chapter 2

Review of the Literature

The Thought Behind Student Misconduct

Researchers Karp and Allena (2004) find that student misconduct is embedded in

five different but interconnected dimensions. First, college consists of a fast and radical

loss of supervision before freshmen have developed strong internal controls that help to

regularize their behavior (Karp & Allena, 2004). Second, freshmen are generally anxious

to make friends and connections so they may feel pressured to drink underage or try

illegal drugs in order to fit in (Karp & Allena, 2004). Third, student culture differs from

the law in regards to illegal drug use and underage alcohol consumption (Karp & Allena,

2004). Fourth, since there is a lack of internal controls among college students, colleges

and universities are forced to increase surveillance and punitive sanctions in order to gain

compliance with school policies (Karp & Allena, 2004). “Fifth, because a quarter of the

student body is new each year, disciplinary approaches must be educational and ongoing

(Karp & Allena, 2004: 6).” Due in part to the loss of supervision and the need to fit in,

college students have been engaging in alcohol and illegal drug use for many years. As

the research states, student conduct must be constantly changing and focusing on

teaching the student (Karp & Allena, 2004). This idea, however, was not always the case.

In the subsections to come, I will discuss the history of student conduct, the Drug Free

Schools and Communities Act, deterrence theory, restorative justice practices, how

Rowan compares to other schools, and introducing the CAS assessment tool.

13

The History of Student Conduct

The approach to regulating student conduct at colleges and universities has grown

and changed over the years. The process really began with colonial colleges in which the

school acted in loco parentis (in the place of the parent) and focused on the personal and

intellectual development of the student (Karp & Allena, 2004). The punishments for

breaking a school policy were typically very violent, such as whippings or “cuffings,”

where a student would get hit on both of their ears, and occurred in front of other

classmates (Karp & Allena, 2004). Harsh and violent punishments continued until the

nineteenth century when less harsh and more educational sanctions began (Karp &

Allena, 2004). The nineteenth century also marked the beginning of the formal discipline

process within higher education as the student started to gain a little bit more respect

from the administration (Karp & Allena, 2004). This meant that there were now student

conduct offices instead of the job of disciplinarian falling onto faculty members or deans

(CAS, 2009b). The German university system began after the Civil War and continued

with mild punishments and fair discipline practices as the school focused more on

research and intellectual growth than student behavior (Karp & Allena, 2004).

Following World War II, schools had a high number of older and more mature

students due to the GI Bill and other federally funded programs, which resulted in the

administration giving the students more respect (Karp & Allena, 2004). Schools became

more diverse after the civil rights movement, during this time, and a students’ rights

movement then followed (Karp & Allena, 2004). In the 1960s, federal law mandated a

fair and consistent judicial process for students, of which put an end to in loco parentis

and once again required more punitive, as opposed to educational, punishments (Karp &

14

Allena, 2004; CAS, 2009b). The Council for the Advancement of Standards in Higher

Education (2009b: 3) states, “In the early 1970s, the American College Personnel

Association established Commission XV, Campus Judicial Affairs and Legal Issues, to

meet the needs of this emerging [student conduct] profession.” Since then, there have

been many emerging standards and laws regarding student conduct such as the Drug Free

Schools and Communities Act.

Drug Free Schools and Communities Act

Many schools have similar drug policies to Rowan University; this similarity is

due to the State of New Jersey regulations and the fact that Rowan’s policies are built

around policies at other institutions. The Associate Dean for Civic Involvement and

Assistant Dean of Students Joe Mulligan created the current Alcohol and Other Drug

Policy (2008) for Rowan University when Richard Jones became the Interim Associate

Vice President and Dean of Students in 2008 (Mulligan, 2011). Working within the NJ

state system, he looked at drug policies at other state institutions and tailored them to fit

the needs of Rowan (Mulligan, 2011). There are also mandatory policy disclosures that

are required under the Drug Free Schools and Communities Act that he included in the

policy (Mulligan, 2011).

Due to the illegality of drugs and underage drinking, along with their known side

effects, the Drug Free Schools and Communities Act began in 1989 and is still in effect

today (Higher Education Center, n.d.). Part 86 of the Education Department General

Administrative Regulations (Higher Education Center, n.d.) is the Drug and Alcohol

Abuse Prevention Regulations, which says:

15

As a condition of receiving funds or any other form of financial assistance under

any federal program, an institution of higher education must certify that it has

adopted and implemented a program to prevent the unlawful possession, use, or

distribution of illicit drugs and alcohol by students and employees.

In order to properly follow the regulations, an institution of higher education must

implement a drug prevention program that prohibits the unlawful possession, use, or

distribution of illicit drugs and alcohol by all students and staff while on campus and

participating in of any school activity (Higher Education Center, n.d.). According to the

Drug and Alcohol Abuse Prevention Regulations (Higher Education Center, n.d.), the

school’s drug prevention program must:

1. Annually notify each employee and student, in writing, of standards of

conduct; a description of appropriate sanctions for violation of federal, state, and

local law and campus policy; a description of health risks associated with AOD

use; and a description of available treatment programs.

2. Develop a sound method for distributing annual notification information to

every student and staff member each year.

3. Conduct a biennial review on the effectiveness of its AOD programs and the

consistency of sanction enforcement.

4. Maintain its biennial review material on file, so that, if requested to do so by

the U.S. Department of Education, the campus can submit it.

Rowan University accomplishes these tasks by creating the Student Handbook, which

includes relevant resources within the Alcohol and Other Drugs Policy Guide. As

previously stated, the Student Handbook is available both online and as part of an agenda

book which is handed out to every student. Additionally, the Associate Dean for Civic

Involvement/Assistant Dean of Students sends out an email once a semester to all

students, which discusses the Student Handbook in detail and how to access it. Even

with mandatory rules and regulations, colleges and universities are able to create their

16

own policies that can vary greatly between schools. Most policies are either based on

deterrence theory or the use of restorative justice practices.

Deterrence Theory

Many college and university policies, such as that of Rowan University, are based

on deterrence theory. Deterrence theory says that individuals are deterred from crime if

they believe that punishment is swift (i.e. given quickly), certain (i.e. assurance that you

will receive a punishment for committing a crime), and severe (i.e. harsh) (Beccaria,

1764/1963). According to deterrence theory, swift, certain, and severe punishments will

deter behavior both specifically and generally.

Specific deterrence refers to the criminal refraining from committing another

crime because of the fear of additional punishment. This study looked at specific

deterrence via survey two, which was a survey given out to drug policy violators, for

illegal use and/or possession of drugs or drug paraphernalia, at Rowan University (see

Appendix B). The violators were asked if they were deterred by the policy after being

caught and sanctioned for their violation. On the other hand, general deterrence refers to

others refraining from crime due to fear of receiving the same harsh punishment as the

previous offender. Specific deterrence involves an offender being deterred by their own

experience while general deterrence involves an offender’s experiences deterring others.

This study looked at general deterrence via survey one which was a survey that was given

out to current Rowan University students (see Appendix A). Survey one asked students if

they knew of anyone who had violated the drug policy before and then asked if they were

deterred by it. This helped to gain insight on the policy’s general deterrence. This study

17

looked at specific deterrence via survey two which was a survey that was given out to

drug policy violators from 2005-2011 (see Appendix B). Survey two asked students if

they were deterred by the policy and the sanctions that were imposed on them. In theory,

Rowan’s drug policy affects both specific and general deterrence.

There is not one deterrence theory that is universally accepted as complete

(Williams & Hawkins, 1986). Since the early 1970s researchers have found that severity

of sanctions has little to do with a person's involvement in criminal activity and that

certainty is the most important component of deterrence (Saltzman, Paternoster, Waldo,

& Chiricos, 1982). Researchers Williams & Hawkins (1986: 549) explain their findings,

“While the magnitude of the association varied across studies, investigators consistently

found a negative association between perceived certainty and self-reported involvement

in crime.” That is, if there is a high-perceived certainty of someone getting caught and

punished for their actions then that person is less likely to commit the crime. Researchers

have since been editing deterrence theory to omit certain characteristics, such as severity,

and add others, such as perception.

Researchers of perceptual deterrence think that deterrence stems from the threat

and fear of punishment as opposed to the punishment itself (Williams & Hawkins, 1986;

Saltzman, et al., 1982; Jensen, Erickson & Gibbs, 1978). This means that deterrence is a

subjective occurrence, as opposed to a calculation that can objectively be applied to every

reasonable person. Kirk Williams and Richard Hawkins (1986: 547) explain that this is

“a theory about the behavioral implications of subjective beliefs.” In order for the

perception of punishment to be close to the reality of punishment, making it a little bit

more objective, information regarding sanctions must be accurate and easily accessible to

18

everyone (Kleck, et al., 2005). If this does not hold true, and someone’s perception of

punishment is low, then that person’s level of deterrence will not increase with just an

increase in potential punishments (Kleck, et al., 2005).

Researchers used the Bureau of Justice Statistics' National Judicial Reporting

Program (NJRP) to find the number of convictions among adults, the number of

convicted adults who received prison sentences, the average maximum sentence imposed,

and the average number of days between arrest and sentencing, in order to estimate actual

levels of certainty, severity, and swiftness of punishments in a given county (Kleck, et al.,

2005). Perception levels were measured by interviews with 1,500 adults spread between

each county represented in the NJRP. The study found that there was generally no

association between perceived and actual punishments, in regards to swiftness, certainty,

and severity, which muddles deterrence effects (Kleck, et al., 2005). This means that

increasing punishment may not increase deterrence and decreasing punishment may not

decrease deterrence, unless the perception of punishment increases or decreases as well

(Kleck, et al., 2005). This study tests perceptual deterrence among both the general

student population at Rowan and the drug policy violators by asking what they think their

chances are of getting caught/caught again for a drug policy violation and if they are

deterred by the drug policy. If a person believes that there is a high certainty of getting

caught and punished for their deviant behavior, then they will likely be deterred from the

behavior.

When looking at severe sanctioning, arrest or other serious punishments have

three main deterring components: stigmatization, attachment costs, and commitment

costs. Stigmatization is when a person is deterred from committing a criminal act

19

because they anticipate very negative reactions from others for committing the crime

(Williams & Hawkins, 1986). Conversely, peers may not react negatively to the crime

itself but will react negatively toward the perceived sanctions, which will deter the

individual from committing the crime (Williams & Hawkins, 1986). For instance,

college peers may think that smoking marijuana is okay but will react negatively toward a

person if they are arrested for it. The survey in this study, given to Rowan’s general

student population, included several questions regarding potential stigmatizations. For

instance, the survey asked respondents if having their parents find out would deter them

from violating the policy; a separate question asked about having their peers find out.

However, in order to get a real sense of stigmatization, we would need to know how their

parents and/or peers felt about the behavior. Attachment costs refers to the perception of

losing attachments (i.e. personal relationships) due to the punishment (legal controls) or

the criminal act itself (extralegal controls) (Williams & Hawkins, 1986). The survey

questions mentioned previously also refers to potential attachment costs. Commitment

costs refers to the perception of losing past accomplishments or jeopardizing future ones

(Williams & Hawkins, 1986). Commitment costs are especially prevalent in the

population of this study, college students, because graduation is an end goal for everyone

in the population and having too many policy violations could jeopardize that goal. In

this study, the survey given to Rowan’s general student population includes many

questions regarding various commitments, in order to get a better understanding of

deterrence. The survey asked students if they are a member of a club, a member of a

Greek organization, a member of an athletic team, and if they have a part-time or full-

time job. These are all potential commitments costs if a student violations policy. If any

20

of these three deterring components, stigmatization, attachment costs, and commitment

costs, are perceived to be very high by an individual, than that person may be deterred

from committing a criminal act, even if their perception of certainty of getting caught

and/or punished is low (Williams & Hawkins, 1986).

Rowan University has based their drug policy off of deterrence theory; the

punishments are swift and severe and the students are perceived to have a high level of

certainty of getting caught. Rowan’s policy is considered severe because students lose

their on-campus housing after their first drug offense involving illicit drugs; however,

studies have found that this may not be the best practice (APA, 2008). Past research has

found that removing delinquent students from school, or housing, labels students as

criminals, which could actually increase their violations (APA, 2008). Labeling theory

was originally extracted from Emile Durkheim’s book entitled Suicide written in 1951 but

made well known by Howard Becker in 1963 (Davis, 1972). This theory states that once

people are labeled as offenders, they are likely to continue offending (Davis, 1972). In

schools, people who are labeled as the “bad students” tend to lash out more than others,

due to the title alone (Davis, 1972). In order to not label students as offenders and to

offer a more educational experience for them, many schools base their policies off of

restorative justice practices.

Restorative Justice Practices

Many laws regarding student conduct at the collegiate level were recently

instated. The Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act was established in 1974, in

1988 the Association for Student Judicial Affairs was founded (now known as the

21

Association for Student Conduct Administration), and there were many Higher Education

Amendments, such as that of the Student Right-to-Know and Campus Security Act (CAS,

2009b). After the establishment of Commission XV, and the laws listed above, there has

been a trend of making the sanctions educational again and focusing on less legalistic

practices and more educational practices such as restorative and therapeutic justice (Karp

& Allena, 2004; CAS 2009b). However, not all schools have followed this recent trend

and continue to have harsher sanctions.

One of the relatively new approaches to sanctioning is utilizing restorative justice

practices in the college setting. Restorative justice involves viewing a specific crime as

harm done to a person or a community (Zehr, 1997). Sanctioning is a collaborative effort

between the victim/community and the offender; thus, the offender is held accountable

for his/her actions and the victim/community’s needs are met (Zehr, 1997). For instance,

there are some schools who believe that mandatory minimum fines are a deterrent to

students and others who do not think that this will decrease violations, so they utilize

educational sanctions such as community service, mandated educational courses, and

various other sanctions (Grasgreen, 2012). Restorative justice has become increasingly

popular among student conduct within colleges and universities (Karp, 2013).

Restorative justice practices aim to have the offender take responsibility for their actions,

repair the harm done to the victim/community, and reduce the risk of re-offending by

building community ties (Karp, 2013). Again, this is done with collaboration between the

victim/community, the offender, and a trained facilitator (Zehr, 1997; Karp, 2013).

There are four common restorative justice practices among student conduct within

colleges and universities: Restorative Justice Conferences, Restorative Justice Circles,

22

Restorative Justice Boards, and Restorative Justice Administrative Hearings (Karp,

2013). A Restorative Justice Conference is when a trained facilitator guides a discussion

between the offender and the victim to come up with sanctions on their own (Karp,

2013). A Restorative Justice Circle is the same as the conference; however, this will

involve holding an object to determine who can speak at that time (Karp, 2013). A

Restorative Justice Board is when there is a board of students, faculty, and staff members

who determine the sanctions with the offender; the victim is invited but does not need to

be present (Karp, 2013). Finally, a Restorative Justice Administrative Hearing consists of

incorporating restorative justice practices into administrative hearings; the offender and

the hearing officer will determine the harm done and how the offender can repair the

harm (Karp, 2013). Over 30 colleges and universities have begun using restorative

justice practices, and while there has not been much completed evaluative research on

this topic yet, the results are expected to be very positive (Lofton, 2010). Schools that

focus more on educational rather than punitive sanctions include but are not limited to;

Dartmouth College in New Hampshire, Southern Technical College in Florida, which

does not allow alcohol on their campus, Cabrini College in Pennsylvania, Eastern

Mennonite University in Virginia, Rutgers University in New Jersey, and Skidmore

College in New York (Trustees of Dartmouth College, 2012; Southern Technical Institute,

2012; Cabrini College, 2012; Lofton, 2010; Karp, 2013).

When discussing the implementation of drug policies, Munro and Midford (2001)

surmise that policies that include less drug education and more punitive sanctions, do not

actually affect drug use among students. It seems that Rowan students feel the same way;

the tagline for the Students for Sensible Drug Policy club at Rowan University is

23

“Educating and creating change to reduce drug use” (Simmons, 2010). The club

continues to push for drug education for their fellow students by sponsoring multiple

drug education workshops (Simmons, 2010). One of the studies that tested the effect of

more educational programs, although not at a college or university, is an evaluation of the

National Drug Strategic Plan in Australia from 1993-1997 (Single & Rohl, 1997). The

National Drug Strategic Plan was created in 1993 with three goals: 1. To minimize the

level of illness, disease, and injury associated with alcohol and illegal drug use, 2. To

minimize the level and impact of criminal drug offenses, drug related crime, violence,

and antisocial behavior within the community, 3. To minimize the level of personal and

social disruption, quality of life, loss of productivity, and economic costs associated with

inappropriate alcohol and illegal drug use (Single & Rohl, 1997). These goals are to be

accomplished by focusing on both prevention and rehabilitation techniques (Single &

Rohl, 1997). Some of the activities/programs that were implemented include the

development of a national statement on marijuana, public education and awareness

campaigns, the National Initiatives in Drug Education Program, new treatment services,

and more (Single & Rohl, 1997). These initiatives were tested by the distribution of

household surveys throughout the five years of 1993-1997; the results, however, were

mixed (Single & Rohl, 1997). There were decreases in tobacco use, increases in

responsible drinking, and no significant trend in relation to illicit drug use, except

however, marijuana use which slightly increased (Single & Rohl, 1997). Even with the

current research, there is a clear need for more evaluative studies of efforts to curb drug

use, especially college and university policies.

Some institutions try to make sanctioning an educational experience while other

24

schools are more focused on punitive punishments. There is a strong need for empirical

research as to which approach is more effective. David Lewis, M.D. (2001) believes that

most harsh punishments do not deter students from using drugs; they simply push the

crime off-campus, which is known as crime displacement. He states that school policies

that completely prohibited underage drinking and illegal drug use may not have created a

safer environment for students, or the surrounding area, because students then take their

illegal activity off-campus (Lewis, 2001). In fact, student drug use could actually

increase off-campus. This is especially true if they do not think the Student Code of

Conduct applies to students living off-campus. Illegal drug use could also increase

because off-campus students do not fear being evicted from on-campus housing, which is

the sanction that upsets the most drug policy violators who live on-campus. In terms of

sanctioning, Lewis (2001) believes that schools should focus more on disallowing

negative behavior associated with drug use (such as assault, sexual misconduct,

vandalism, etc.) and less about the drug use itself.

Rowan University Policies vs. Other Schools’ Policies

Even though many colleges and universities have a similar drug policy to Rowan

University, some students believe Rowan's policy to be very severe (Simmons, 2010).

According to the Student Handbook (2011: 49), the recommended sanction for a first

violation of the drug policy, as it pertains to illegal use and/or possession of drugs or drug

paraphernalia, is a “$400 fine, completion of substance screening, community restitution

hours, disciplinary probation, suspension of campus housing privileges, and

parent/guardian notification.” The recommended sanction for a second violation is “a

25

$500 fine, completion of substance screening, disciplinary probation (remainder of

academic career), University suspension and parent/guardian notification” (Rowan

Student Handbook, 2011: 50). The recommended sanction for the third violation is

“University suspension or expulsion and parent/guardian notification” (Rowan Student

Handbook, 2011: 50). The recommended sanctions are different for alcohol-related

violations. The recommended sanctions for the first violation of an alcohol-related

incident, as it pertains to underage possession or use, is “$150 fine, completion of

Alcohol and Other Drugs education program, community restitution hours, disciplinary

probation, and notification of parent/guardian” (Rowan Student Handbook, 2011: 173).

As seen, the difference between a first violation of the illegal drug use and/or possession

policy and a first violation of the underage alcohol use and/or possession policy is a $250

fine increase and the loss of campus housing privileges, which does not come until the

third violation of the underage alcohol use and/or possession policy. This study

specifically focused on the illegal drug aspect of Rowan University’s drug policy. While

many schools have similar policies to Rowan University, there are other college and

universities with differing drug policies.

Binghamton University for example, a public university in New York, takes a

different approach to punishment. Binghamton separates their drug policy sanctions by

three different drug types: marijuana related charges, illegal prescription drug charges,

and other drug charges (Office of Student Conduct, 2010b). Table 1 represents the

recommended sanctions for “possession/personal use of marijuana, possession of drug

paraphernalia with marijuana residue, and purchasing or attempting to purchase a small

amount of marijuana” at Binghamton University (Office of Student Conduct, 2010b).

26

Table 1

Marijuana Related Charges at Binghamton University

Recommended Sanctions

1

st

violation 1 year disciplinary probation (may include, but is not limited to,

educational sanctions, community service, and removal from housing

and/or loss of privileges) and Marijuana 101 (an online drug education

course that takes about two hours and costs $50 to complete)

2

nd

violation Disciplinary probation until graduation, relocation if appropriate, loss

of visitation to appropriate area, educational sanction x 3 (Educational

sanctions “consist of writing an essay, attending and/or presenting a

workshop to a group of students, etc., with specific instructions to be

included in the sanction letter”), and parental notification if relocated

3

rd

violation Final probation until graduation, removal from all university housing,

loss of visitation to all residential areas, and parental notification

Educational sanctions “consist of writing an essay, attending and/or presenting a

workshop to a group of students, etc., with specific instructions to be included in the

sanction letter” (Office of Student Conduct, 2010b). Also, disciplinary probation may

include, but is not limited to, educational sanctions, community service, and removal

from housing and/or loss of privileges (Office of Student Conduct, 2010b). According to

Binghamton University's Sanction Guidelines, removal of campus housing occurs after a

student's third drug offense (Office of Student Conduct, 2010c). Table 1.1 shows the

recommended sanctions for possession, use, purchasing, or attempting to purchase

prescription drugs prescribed to another (Office of Student Conduct, 2010b).

27

Table 1.1

Illegal Prescription Drug Charges at Binghamton University

Recommended Sanctions

1

st

violation

2 years disciplinary probation and educational sanction x 2

2

nd

violation

Disciplinary probation until graduation, relocation if appropriate, loss of

visitation to appropriate area, educational sanction x 3, and parental

notification if relocated

3

rd

violation

Final probation until graduation, removal from all university housing, loss

of visitation to all residential areas, and parental notification

Table 1.2 shows the recommended sanctions for “possession/personal use of other

drugs, possession of drug paraphernalia with residue other than marijuana, and

purchasing or attempting to purchase other drugs” at Binghamton University (Office of

Student Conduct, 2010b).

Table 1.2

Other Drug Charges at Binghamton University

Recommended Sanctions

1

st

violation Disciplinary probation until graduation, educational sanction x 3, and

parental notification

2

nd

violation 1 year suspension and parental notification

3

rd

violation Required reflective paper and interview, final probation until

graduation, removal from all University housing, and loss of visitation

to all residential areas

28

Binghamton University's policy may be different than Rowan's due to the fact that

marijuana has been decriminalized in New York. By 1979, eleven states within America

decriminalized possession of small amounts of marijuana, including New York

(Earleywine, 2002). Although this may be the reason for the less strict drug policy at

Binghamton, some schools in states in which marijuana is illegal have similar policies.

The University of San Francisco Division of University Life completed a program review

in 2008 for their Office of Student Conduct, Rights, and Responsibilities (USF, 2008).

Part of the program review involved collecting data from other institutions. The

institution compiled a list of sanctioning for first and second illicit drug offenses for

seven different religiously affiliated, private institutions that compare to the University of

San Francisco (USF, 2008). The seven schools that were compared to the University of

San Francisco are: Gonzaga University in Spokane, Washington, Loyola Marymouth

University in Los Angeles, California, Santa Clara University in Santa Clara, California,

Boston College in Chestnut Hill, Massachusetts, Seattle University, in Seattle,

Washington, Georgetown University in Washington, D.C., and Loyola University of

Chicago in Chicago, Illinois (USF, 2008).

When looking at the sanctioning for all eight institutions, Boston College and

Loyola University of Chicago are the only schools that require housing suspension for a

first time illicit drug offense; even still, University of Chicago does not require housing

suspension for possessing drug paraphernalia or being in the presence of a controlled

substance (USF, 2008). For all of the other institutions, the first illicit drug offense

results in housing probation and removal from on-campus housing occurs after the

second drug offense (USF, 2008). Other sanctions for a first time illicit drug offense

29

include fines of up to $250 but averaging at $50, parental notification with the students

writing a letter to their parents and the office of student conduct also sending a letter

home, drug testing (only at Loyola Marymount University), and educational sanctions

(USF, 2008). The educational sanctions include behavior assessment, counseling, ethics

workshop, educational research project, enrollment in a weekly Drugs and Alcohol

seminar group, community service hours, e-toke (marijuana-specific assessment and

feedback tool), Brief Motivation Information meeting, and drug abuse assessment

program (USF, 2008). Clearly, some schools take a more educational approach to

sanctioning.

Distribution of Policies: Rowan vs. Binghamton University

In addition to the policies and sanctions, the way college and universities

distribute their policies can affect a possible deterrent effect. For example, distributing

policies through email may be an extremely effective method or not at all, depending on

if students regularly check their email or not at that institution. Without evaluating

student awareness of policies, there will be a lack of insight on whether or not

distribution methods are the most effective. Gaining data on student awareness, along

with student perception, of such policies will be very beneficial as it is a piece of

information that is currently missing.

The school’s policies and the judicial process must be easily accessible to students

(Karp & Allena, 2004). Students should understand the policies and the judicial process;

the judicial process should also remain fair and consistent (Karp & Allena, 2004). The

way policy information is distributed differs among schools. Rowan University utilizes

30

many different ways to communicate the current policies. First, the Student Handbook

(containing both the Student Code of Conduct and the Alcohol and Other Drugs Policy) is

located online as a part of the Office of Community Standards and Commuter Services’

website. Second, all students and parents are told about Rowan’s policies during the new

student orientations in the summer months leading up to the start of the fall semester.

Third, the Student Handbook is put in an agenda book that is given to every current

student. Fourth, Resident Assistants have floor meetings with all of their residents

(students living on-campus) and go over the policies with them. Finally, the Office of

Community Standards and Commuter Services sends an email once a semester to all

faculty, staff and students explaining the Student Handbook and giving a link to its

location on their website. Essentially, if a student does not go to freshmen orientation or

the first floor meeting held by their RA and does not read the Student Handbook (either

online or in paper form), then they will not know the Alcohol and Other Drugs Policy at

Rowan. This is how Rowan informs their students; other schools take different

approaches.

Binghamton University informs their students of policies in a different way than

that of Rowan University. In addition to distributing information through pamphlets,

orientation materials, and by Resident Assistants, Binghamton University also has a

student-run club that helps to distribute information about policies and sanctions for

policy violations (Office of Student Conduct, 2010a). The Student Conduct Outreach

Team (SCOT) promotes awareness of campus policies, discusses the philosophy of the

Student Conduct Office, talks about the judicial procedures, and encourages responsible

decision-making (Office of Student Conduct, 2010a). According to Binghamton's Office

31

of Student Conduct website (2010a), “You can find SCOT performing door-to-door

residential educational initiatives... educating campus constituents at various campus

events, partnering with other student organizations, and hosting conduct themed parties.”

While there are different tactics that can be used to disseminate information to a

large group of people, such tactics have also not been fully examined. The purpose of

this study was to empirically evaluate the policy’s effectiveness in terms of recidivism;

however, student awareness was also an important feature to better understanding the

policy’s possible deterrent effect and to ensure that the information was being given to

the appropriate people.

CAS Assessment Tool

One valuable assessment tool comes from the Council for the Advancement of

Standards in Higher Education (CAS). This council created self-assessment guides for

forty-three different departments/services within a college or university. The two self-

assessment guides of the most importance to this study are for Alcohol, Tobacco, and

Other Drug Programs and Student Conduct Programs. All of the CAS guides are

comprised of fourteen parts for assessment: Mission, Program, Leadership, Human

Resources, Ethics, Legal Responsibilities, Equity and Access, Diversity, Organization and

Management, Campus and External Relations, Financial Resources, Technology,

Facilities and Equipment, and Assessment and Evaluation (CAS, 2009a; CAS, 2009b).

The assessments are to be completed by a task force made up of faculty members, full-

time staff members, and students (USF, 2008). Completing a CAS self-assessment can

offer very beneficial information about a school’s department or program.

32

Stephen F. Austin State University (SFA), a public institution in Nacogdoches,

Texas, completed the CAS self-assessment for Alcohol, Tobacco, and Other Drug

Program in 2009. One specific question on the assessment states, “What evidence is

available to confirm achievement of program goals? (2009: 4)” and SFA concluded,

“Currently little evidence is available based on our assessments” (SFA, 2009: 4). Results

of the self-assessment also showed SFA that there is not a strong effort to educate

students on the consequences of violating the school’s policies, along with a lack of

educating students on the dangers of unsafe drinking and drug use (SFA, 2009).

University of San Francisco (USF), a private institution in San Francisco, California,

completed a CAS self-assessment on their Office of Student Conduct, Rights, and

Responsibilities in November of 2008. While USF (2008) found a multitude of strength

areas, there were also areas that needed to be improved. Some of the items to maintain or

improve upon include continuing to “evaluate the effectiveness of educational sanctions”

(p. 3), increasing the quantity and quality of student learning outcome evaluations,

expanding on programming, re-evaluating the use of conduct boards, and providing more

follow-up with students and the community (USF, 2008). Clearly, the CAS self-

assessments provide helpful information that will only improve a department or program;

however, the assessments still lack crucial information.

While it would be extremely constructive for Rowan to complete a CAS self-

assessment for its Community Standards Office, there are still missing components to that

particular evaluation. For instance, it asks if “the campus community is informed of the

judicial programs” (part 1 section 2.11) but it does not ask how that information is being

distributed and if their efforts of distributing information is effective (USF, 2008). In

33

addition, sanctions are not discussed and recidivism rates are not calculated (USF, 2008).

The self-assessment generally focuses on if the department or program is upholding the

institution’s mission statement, if they are meeting all of the requirements, if the students

are learning and growing, and if the department or program needs more resources to be

able to function better (USF, 2008). The assessment does not focus on if specific

sanctions are effective, if students are knowledgeable of the policies, and what students’

perceptions of the policies are, all of which are very important aspects of evaluative

student conduct studies (USF, 2008). There is a strong need for a more in-depth

evaluation of institutions’ student conduct departments, especially that of Rowan

University’s Community Standards Office.

Summary of the Literature Review

Karp and Allena (2004) find that student misconduct, such as alcohol and illegal

drug use, is embedded in five different dimensions: 1. There is a lack of supervision

before students have developed controls, 2. Students feel pressured to drink alcohol

underage or do illegal drugs in order to fit in, 3. Student culture is at odds with

mainstream society, 4. Colleges and universities are forced to increase surveillance and

punitive sanctions, 5. Disciplinary approaches must be educational and ongoing.

According to various studies, drug use among college students is still very prevalent

today (CAS, 2009; Johnston et al., 2008).

The history of college and university policies shows that they have gone from

violent and harsh to more educational (Karp & Allena, 2004; CAS, 2009b). Today, there

are regulations to such policies to ensure effectiveness. One of these regulations is the

34

Drug Free Schools and Communities Act (Higher Education Center, n.d.). In order to

receive federal funding, the school must: 1. Notify each employee and student of

standards of conduct, description of sanctions, and the health risks associated with

alcohol and illegal drug use including available treatment programs, 2. Develop a method

of distributing information to every student and staff member, 3. Conduct a biennial

review on the effectiveness of its programs and the consistency of sanction enforcement,

and 4. Keep all of that information on file. While there are some regulations for college

and university policies, each school can have very different drug policies. The policies

are usually deterrence based or based on the use of restorative justice practices.

This literature review discussed the differences between deterrence-based policies

and restorative justice-based policies. Deterrence theory says that individuals are

deterred from crime if they believe that punishment is swift, certain, and severe

(Beccaria, 1764/1963). Restorative justice, on the other hand, involves viewing a specific

crime as harm done to a person or a community and focuses on more educational

punishments (Zehr, 1997). Rowan University’s drug policy is deterrence-based, while

schools like Binghamton University have restorative justice-based policies. Up until this

point, there is a lack of research on which type of policies are more effective. While

there have been great evaluative measures created, such as the CAS assessment tool,

there is still a need for further research. This study researched Rowan’s drug policy in

order to determine its effectiveness, along with student awareness and satisfaction of the

policy.

35

Chapter 3

Methodology

Introduction

The purpose of this study was to begin to evaluate Rowan University’s Alcohol

and Other Drugs Policy. Evaluative research is intended to determine if a policy is

accomplishing what it aims to, which in this case was deterrence (Kleck, et al., 2005).

This study, amongst other things, attempted to answer whether or not students were

aware of the policy and if they were deterred by it. A mixed method approach was used

to gain the most amount of information from the two surveyed populations. In the

subsections to come, I will describe the context of the study, sampling procedures,

instrumentation, operational definitions, how I operationalized deterrence and recidivism,

the variables used, and how the data was analyzed.

Context of the Study

This study took place at Rowan University. Rowan is a four-year, public,

suburban, coed, college located primarily in Glassboro, New Jersey (NJ) with a smaller

satellite campus in Camden, NJ (Rowan University Media and Public Relations, 2012).

According to the Rowan Fast Facts 2012-2013 website (2012), the University is

considered medium-sized with 12,183 enrolled students (10,750 undergraduate students

and 1,383 graduate students). Since Rowan University currently has a faculty of 1,049,

the class sizes can typically be kept at an average of twenty students (Rowan University

Media and Public Relations, 2012). Rowan awards fifteen degrees within the colleges of

“Business, Biomedical Sciences, Communication & Creative Arts, Education,

36

Engineering, Graduate and Continuing Education, Humanities & Social Sciences,

Medicine, Performing Arts and Science & Mathematics (Rowan University Media and

Public Relations, 2012). The current price tag for tuition, fees, room and board, as of

August 14 2012, is $23,352 per year for in-state students and $31,158 per year for out-of-

state students, however, 7,883 students received financial assistance in the 2010-2011

academic year (Rowan University Media and Public Relations, 2012).

Sampling

Since this policy had already been in effect, I conducted a cross-sectional study

where I surveyed students in order to examine the potential effectiveness, awareness and

satisfaction of Rowan’s alcohol and drug policy, at one given time (Creswell, 2008;

Ruane, 2005); there was no attempt to follow up with the same respondents. Awareness

and effectiveness of the policy was based on two different populations: the general

student population and those students who have been found in violation of Rowan’s

Alcohol and Other Drugs Policy for possession and/or use of illicit drugs or drug

paraphernalia between 2005 and 2011.

Our target population for the first survey (See Appendix A) was all of Rowan

University’s current students and I was able to send the first survey to that entire

population, although not everyone responded. First, I sent the survey to June Ragone,

Research Analyst for Rowan University’s Institutional Effectiveness, Research and

Planning Department. She then created a SurveyMonkey link to which the survey could

be accessed online. We were able to send our survey to that entire population, about

12,183 students, via the “Rowan Announcer.” The Rowan Announcer is a daily email

37

that is sent to all current students’ Rowan email addresses. In order to post to the Rowan

Announcer, one must be affiliated with a club or organization at Rowan University,

therefore, I partnered with Students for Sensible Drug Policy and they posted the survey

on the Rowan Announcer. The survey was sent out via the Rowan Announcer on specific

days: January 29

th

, February 5

th

, February 12

th

and February 17

th

; however, the survey

remained open from January 29, 2013 until February 28, 2013. The only certain thing

that all of the participants in this first survey had in common was their enrollment in

Spring 2013 courses at Rowan University. Although we were able to send the first survey

to the entire Rowan student population, the response rate was not very high. We had 98

respondents and while some completed the entire survey, many did not answer all of the

questions. June Ragone explained that Rowan students had received a lot of surveys in

their email at that time and perhaps they were over-surveyed.

For the second survey (See Appendix B), a purposive sampling technique was

employed in order to reach all of the students found responsible for violating Rowan’s

drug policy for possession and/or use of illegal drugs or drug paraphernalia between the

years of 2005 and 2011, which consisted of 349 students but only 224 with listed email

addresses. In order to reach out to these students, Joe Mulligan, the Associate Dean for

Civic Involvement and Assistant Dean of Students, gave me a list of Rowan email

addresses for everyone who had violated Rowan’s drug policy from 2005-2011. Mr.

Mulligan heads the Office of Community Standards and Commuter Services at Rowan

University, which is the office that processes all of the student conduct cases. I created a

second survey, again using SurveyMonkey, and sent it out electronically using an email

address that I specifically made for distributing this survey. Some of the people in this

38

population may have been attending classes at Rowan at the time of the survey and some

were not, however, all were students at Rowan University at one time between 2005 and

2011. While the entire second population was sent the survey, there was still not a high

response rate. There were 18 respondents to the second survey and, again, many chose

not to answer every question. This lack of response could be due to many reasons; such

as, people no longer checking their Rowan email after graduating/leaving Rowan or

perhaps not wanting to bring up past incidents.

Instrumentation

Research shows that self-reporting can be extremely helpful in gaining

information on delinquency and criminal activity (Thornberry & Krohn, 2000). There

should be multiple question types used in self-reports including frequency response sets

and open-ended questions (Thornberry & Krohn, 2000). For this study I employed a

mixed methodological approach. The surveys were broken down into four main response

types: yes/no, Likert scale (coded as Strongly Agree, Agree, Neutral, Disagree and

Strongly Disagree), demographic questions and open-ended questions, which allowed for

more opinion-based student input. The questions focused primarily on students’

awareness of the policy and deterrence effects; however, the surveys also included

perception questions, opinion questions, and more. The questions used in both surveys

were adapted from the 2011 National Association of Student Personnel Administrators

(NASPA): Student Affairs Administrators in Higher Education, Assessment &

Knowledge Consortium, along with The Effects of Sanctioning on Underage and

Excessive Drinking on College Campuses (NASPA Student Affairs Administrators in

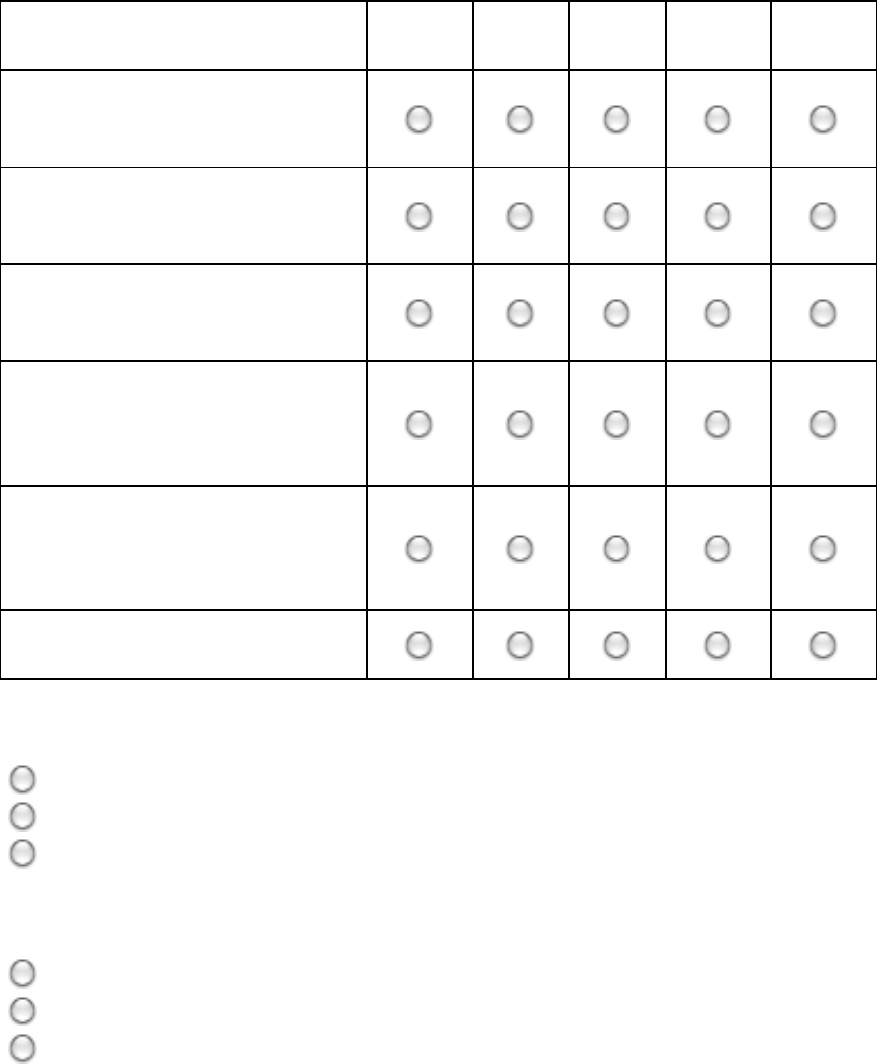

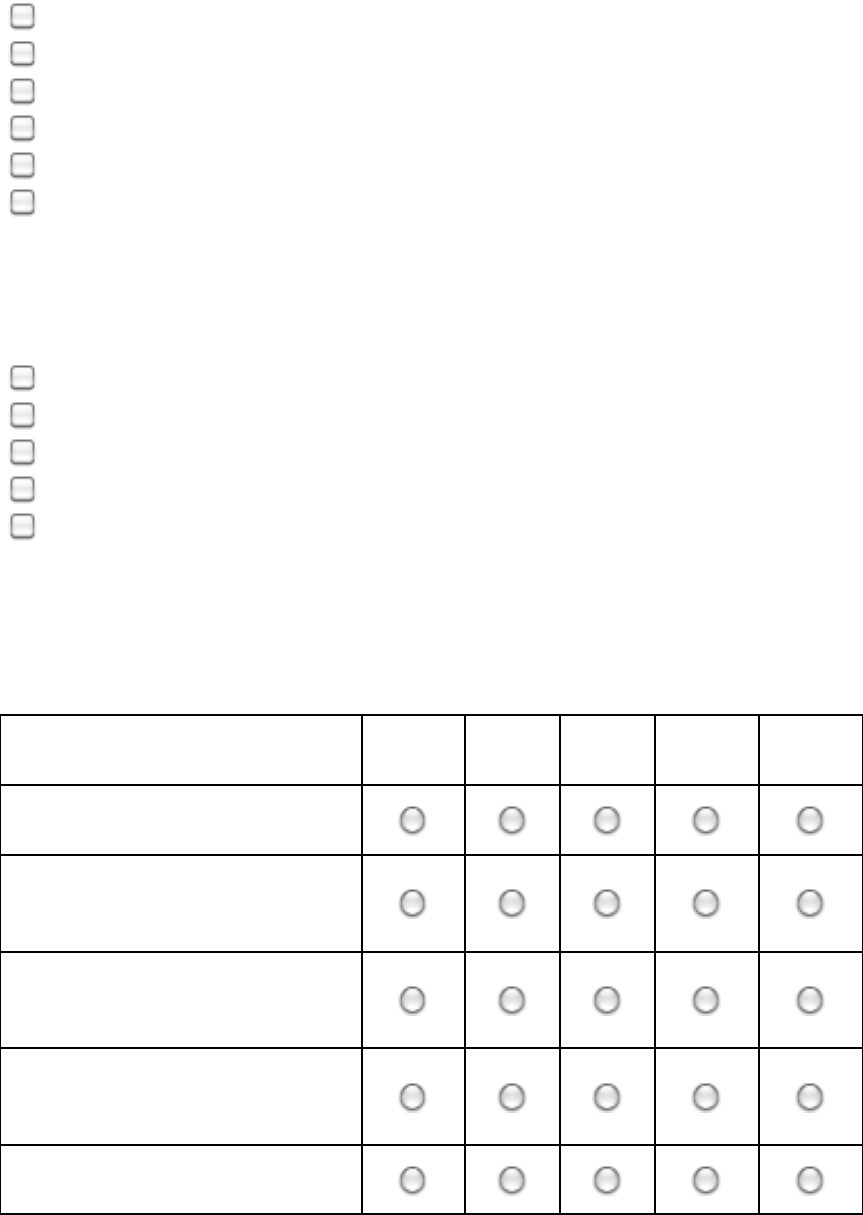

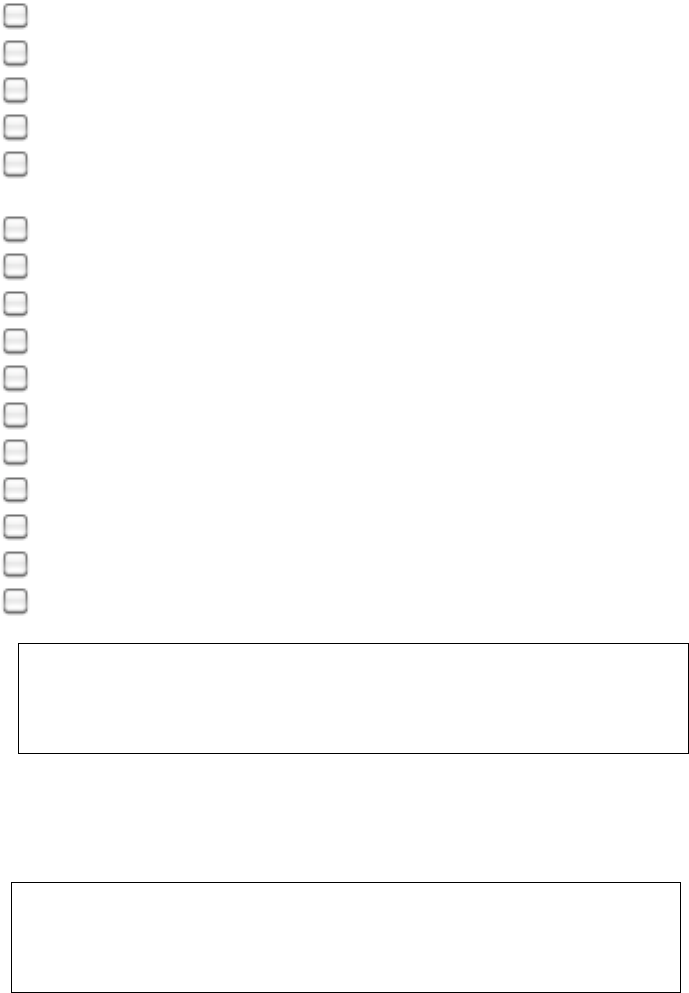

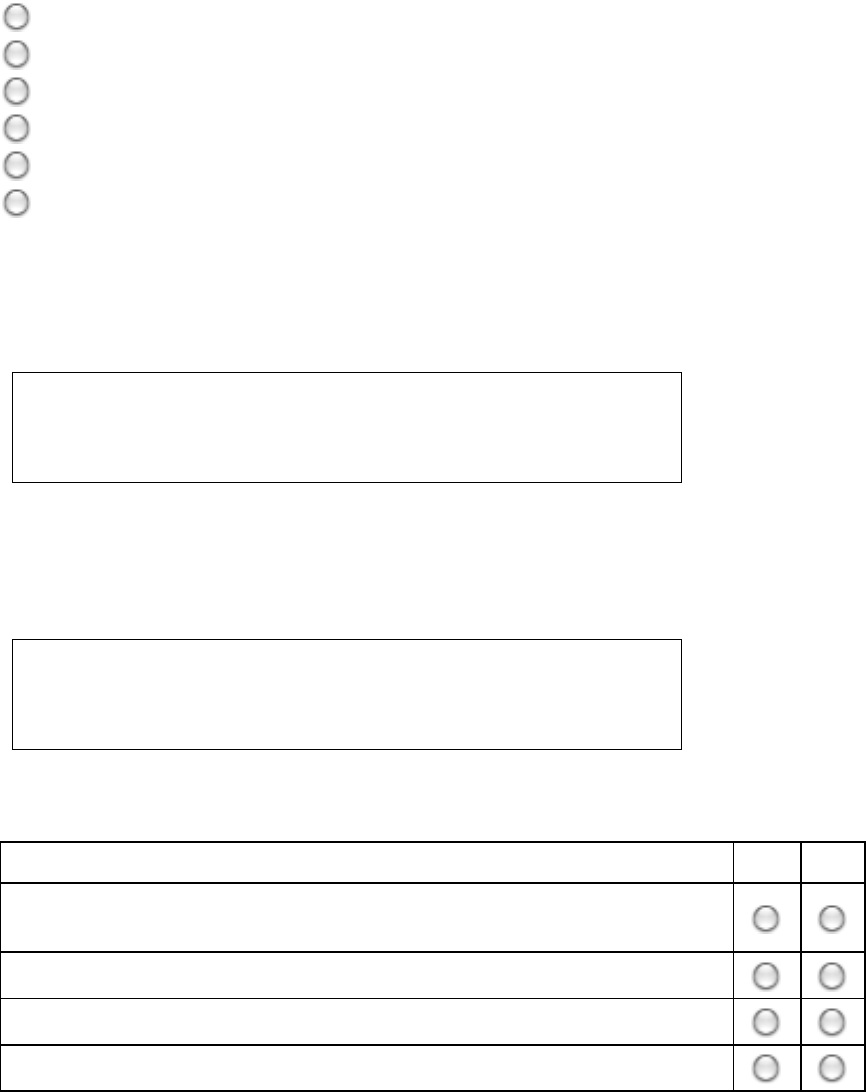

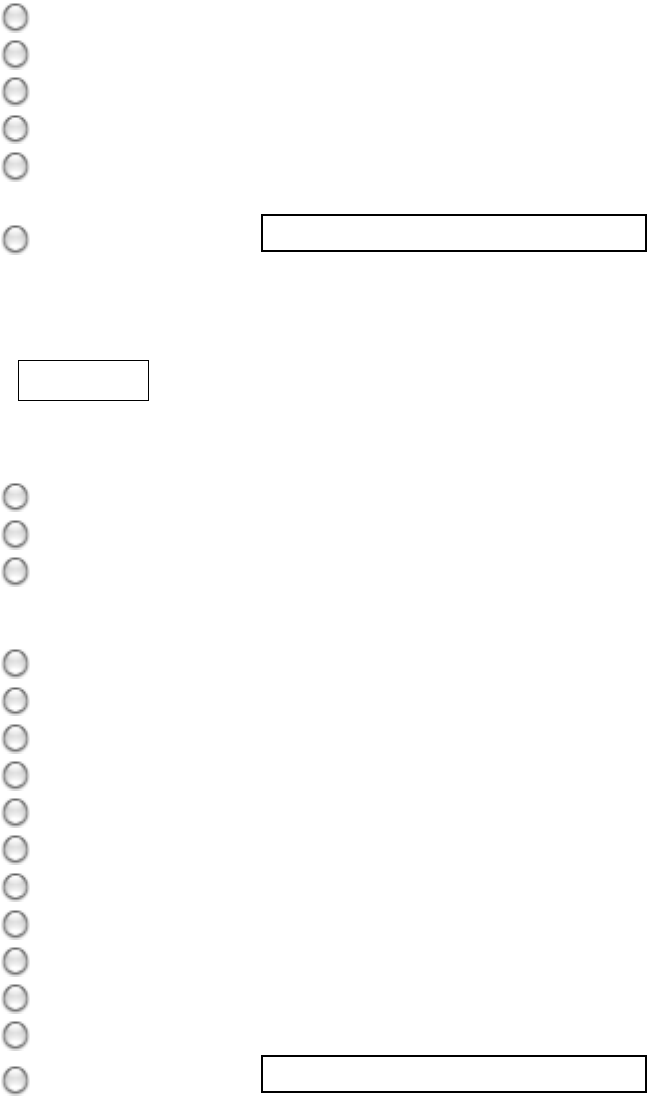

39